By Annie Ryall

https://etsy.me/3gmyUlk

Packing up and sorting my city flat to move to the country I came across a shoulder bag. No ordinary bag, it was made of hand-woven carpet with naturally dyed wool. The strap had become frayed and moth infested. It was time to do a Marie Kondo on it. It didn’t “spark joy” but brought memories flooding back.

After two years living in France from 1975 to 1977, my French anarchist existentialist boyfriend and I decided to return to Australia. We took the overland route from Europe to India on his Suzuki 750 motor bike. Taking this route was a rite of passage for free spirits of the 70s although Georges was the ultimate anti hippy. Easy access to hashish and a transcendental experience were not for him. The bike’s saddlebags smelt permanently of leather and Roquefort cheese with a subtle overlay of red wine.

Turkey delighted us with its rich traditions of Greek, Roman and Ottoman cultures while in Iran we managed to survive a road accident before heading into Afghanistan. There were two routes. One across the north was shorter but more treacherous and one going south was longer but a better road.

Photo courtesy https://www.oldbikemag.com.au

We were within 50km of Kandahar when the bike puttered to a stop. All attempts to start it failed. Georges was furious as only the French can be: “’Fait chier”, “Putain de merde” and other expletives expressed his disgust.

Meanwhile I was starting to panic and felt sick in the stomach. Stranded in the Afghan desert, I had visions of dying from sun stroke and dehydration or another quicker more violent end.

There was nothing for it but to try and thumb a lift into Kandahar.

After about 10 minutes – amazingly – an old tray truck came past and pulled to a halt. I had visions of bandits brandishing Kalashnikovs jumping out but instead two pleasant looking guys wearing the traditional Perahan Tunban – a white loose long top and pants – stepped out to help us; they were very curious about the bike.

We mimed “bike broken” and “need bike repair shop”. Without any fuss they proceeded to lift the wounded Suzuki onto their truck while Georges fussed and clucked over his baby, worrying about how it would cope with this manhandling. Through mentally gritted teeth I thought: “For Christ’s sake Georges, bugger the bloody bike, let’s just get to Kandahar. These lovely guys have stopped to help us. Let’s just be grateful!”

Approaching Kandahar at sunset the truck stopped near a meagre stream, the driver gesturing they needed to pray. After their salat al asr and in the interests of domestic harmony, they used sand and water to wash out the grease from their bike sullied pristine white robes.(!)

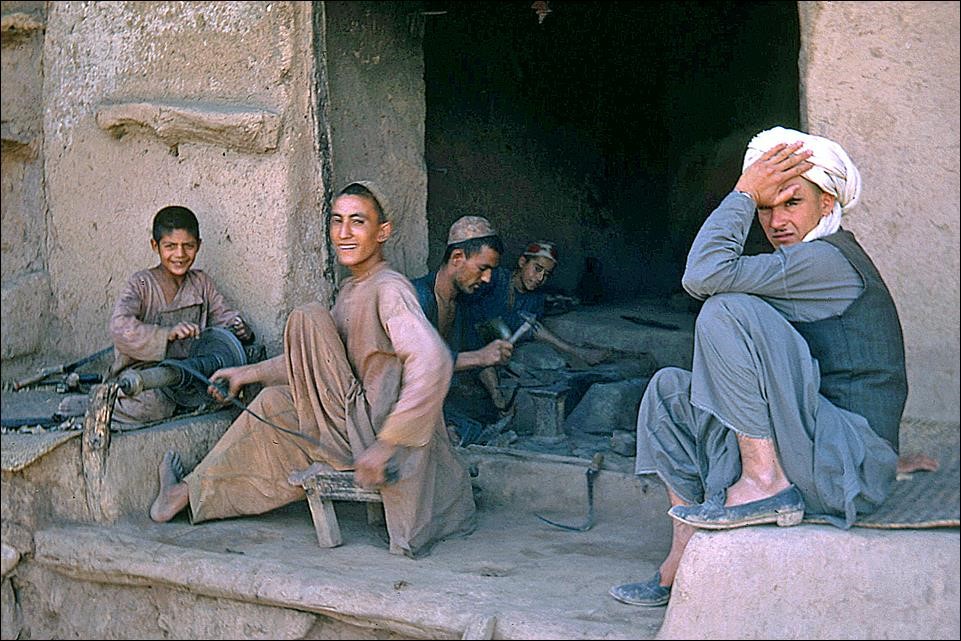

Arriving in Kandahar our friends dropped us and the bike off at the local bike shop. It was not much more than a shack with a hard mud floor. Out the front was a motley collection of old motor bikes – Indians, several old army motorbikes, a Royal Enfield – all in dubious states of repair but valued and a status symbol. So when our 1975 Suzuki Water Cooled (the first of its kind) turned up it was like the iPhone 11 landing in a pre-digital world. Something to be admired and desired.

The mechanic – who wore a kurta and traditional Pamiri hat and looked about 14 – conferred with his colleagues all squatting on the ground around the injured beast. The head mechanic then spoke through the Mullah who was called to be our translator and declared proudly that yes they could fix the bike and held up two fingers.

“Two days? That would be great!”

The Mullah shook his head. “No. He means two weeks”.

We were mortified, but really what choice did we have?

I headed for the grocery shop near our run-down accommodation and was thrilled to find Kraft cheddar cheese and Sao biscuits. These became my staple meal for the time I was there – It made a change from gristly goat’s meat in a tepid bain marie. Georges had a cast iron stomach and could eat anything as long as it was disinfected with red wine. Water was a poor excuse for liquid to him.

The days wore on and every so often we would call in to the “bike shop” to check on progress of our Suzuki. Necessity was truly the mother of creation for these guys. There were no parts available to fix the engine so they fashioned parts out of old jam tins and random washers using the soldering iron to great effect. There were several bare foot boys in kurtas running around helping with the repairs and serving the ubiquitous green tea to customers.

The bike was much discussed and admired in the town. One of those was a young man called Farzaad known to our Hotel owner. He was a man of relative means in Kandahar and he had his eye on the Suzuki – how it could give him status in the community. He kept offering to buy it and Georges would always brush him off – it was like asking for his right arm.

As time wore on and it was 12 days after our arrival Georges was becoming despondent and started talking about taking Farzaad up on his offer and flying back home to Australia even though he had a horror of flying – an indication of his mood.

He finally agreed to sell the bike to Farzaad for $500 and shook hands on it. But two days later when the bike was ready Georges changed his mind. He happened to mention this to the Mullah who was horrified.

“You mean you have agreed to sell your bike to Farzaad and now you are going back on your promise?”

“Well.. yes. Is there a problem with that?”

“Listen to me. Don’t tell anyone about this. You must do exactly as I say or your lives will be in danger.” He made a throat cutting gesture.

“Pack your bags and come to the carpet sellers’ shop. We will hide you and your motor bike in there. You must sleep there tonight and someone will be on guard. Then at dawn we will wake you, give you some food and you must leave. Do as I say and you will be safe.”

Georges was most scornful of this and received it with a Gallic shrug and a “Borf” but the Mullah insisted and I could see that we had to do exactly as he said.

We picked up the bike, thanking the amazingly resourceful mechanic and his crew, then headed for the carpet shop. There, “she” was wheeled in with reverence and sat resplendent amidst piles of carpets and garlands of hanging bags. Seeing the young man standing guard over her, rifle slung casually from his shoulder was still a sharp reminder of the danger of our situation.

After a nervous and fitful night’s sleep we were shaken awake and given a breakfast I could hardly eat. Stomach clenched with fear, I couldn’t wait to get out of there. Would the bike start? Would Farzaad come after us? Had he found out our plan?

Georges kick started once, kick started twice and then on the third go it started. Whew! My heart was pounding.

Just as we were about to make our get away the Carpet Seller’s son came running out of the shop waving something. It was my Afghan shoulder bag! In my panic I had left if behind. I threw it over my shoulder and waved an effusive thank-you. We were finally away.

There followed nail biting hairpin bends through the Khyber pass, curfews in Peshawar, Kamikazi truck drivers in India and a stomach churning trip on a Russian boat from Madras to Perth before we finally arrived in Melbourne.

Not long afterwards it may not surprise you to hear dear reader that I parted ways with Georges. There were 3 of us in this relationship and I knew which one of us had to go. There was simply no contest.

* Check out this fantastic site featured on my Top Picks page:

Jean Claude LaTombe – Travel Blog

** Another terrific travel blog by Matt Karsten featured on my Top Picks page: